When you are 29 years old, you're married and have a small child, you can't just do your academic work, you have to put food on the table for your family. And when you are offered a job, not only one that interests you, but also one that brings in money, you can hardly refuse it. It was for this reason that Dmitrii Ivanovich Mendeleev spent no time in accepting in 1863 the proposal put to him by a quite well-known Russian businessman, Vasilii Aleksandrovich Kokorev, who made an offer that was hard to refuse — to check on the condition of his kerosene factory in Baku, so as to either improve production, or close it down.

The factory was losing Kokorev at least 200 thousand roubles every year, at the same time the world was experiencing a boom in kerosene-source illumination. Something was amiss in the system, and it was Mendeleev's job to find out why money was flowing out of, and not into, the pockets of the owner of an oil refinery at the time of a feverish rise in the popularity of kerosene lamps.

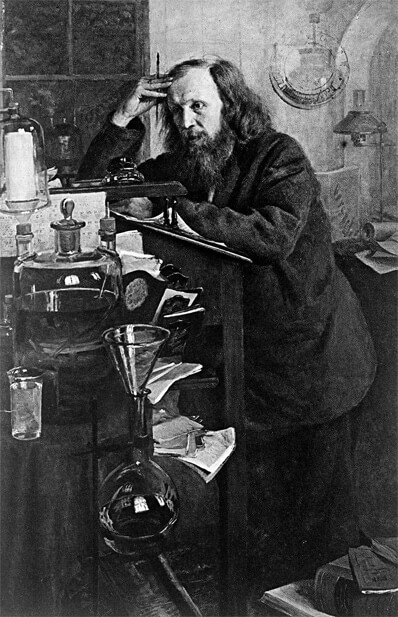

We imagine Dmitry Ivanovich as an old man with a lion's mane of grey hair. But aged 29 he had an athletic build, with a determined nature and a firm grasp of business. His words of wisdom have come down to us today: "turn the air blue left, right and centre and you'll live long!" He literally scoured every single oilfield. What it was he set right in Baku, and what methods he used to sway the management there — this is a separate story. But a year later Kokorev's refinery was running a profit of hundreds of thousands of roubles yearly.

Mendeleev was a true individual and could see things, that others couldn't. Thus, he noticed, that the whole system of extraction, transportation and refining belonged to a museum. Everything needed to be updated. He spoke and wrote about things, his contemporaries just couldn't get their heads round: oil is a liquid, like water, so it should be transported through pipes. Extracting one kilo of kerosene from 330 a ton of oil, and pouring away the rest down the nearest ravine was arrant high-handedness, just like heating up your stove with banknotes.

Though it must be said that, his refusal to continue working for Kokorev because he loved the academic world, was also in a way high-handed. If he had agreed to another 10 thousand roubles on top of 5% of his annual income, he would certainly have been the first person in the world to put into practice his ideas about a pipeline, and tankers... But he remained true to science and therefore his dreams and insights were brought to life by someone else, who that year had only just put on his first school cap.

Nowadays it is common to think, that freedom of behaviour and choice of employment guarantee the emergence of intellectual giants. But our forebears assumed, that only discipline and organization could manufacture a worthy citizen and valued expert out of a loud-mouthed schoolboy.

For this reason the Imperal Moscow School of Engineering was distinguished by its particularly harsh regimen — arguably, those in army barracks today have it cushier. The professors believed, that if a student was forbidden form doing almost anything apart from study, he would dive in to it head first, so as not to go out of his mind. This was the seat of higher learning Vladimir Shukhov entered in 1871, after graduating from grammar school.

Vladimir grew up in a family of modest means, and at that time the career of an engineer was a real possibility of achieving success in life, as engineers were in great demand. The country was experiencing industrialization, and entrepreneurs, wishing to invest capital, were seeking out professionals. Volodya Shukhov, meanwhile, was a very promising student. While still in his third, or second year he devised an atomizer, in other words a spray that would burn up heavy liquid oil: what we know as fuel oil.

It is no surprise, that Shukhov took an interest in oil and everything that was connected with it. By that time Dmitry Mendeleev had discovered the Periodic Table several years earlier, and his active stance in defending the further and extended uses of oil, naturally, was supported by the student body. Their hero had not yet turned 40, and students saw in him an older companion who would lead them forward out of the stagnant world of old science and a blinkered life .

They were particularly incensed, by the bureaucratic red tape that could put a stop to interesting projects. They looked on bitterly, as ideas, expressed by their Guru, were implemented abroad, in the USA. Mendeleev himself was not best pleased. The time of the Russian breakthrough had not yet come. What was needed was an idea, a push.

The time came to leave behind the walls of his alma mater and Vladimir Shukhov received a lavish proposal from Pafnuty Chebyshev, a mathematician with an international reputation : to work together. A twist of fate indeed: in 1863 Mendeleev rejected practical work in favour of science, and in 1876 Shukhov rejected academe to take up practical work.

The question was: how could a talent that wished to leave the ranks of scholars be further encouraged? Or just as well, perhaps, make him change his mind. The School Council decided that a trip to America for a young and up-and-coming engineer would be just the job. Especially as it was not only a trip, but an official assignment to visit the World Exhibition. And who would turn down the opportunity of seeing the world...

By this time 11 years, had passed since the last salvoes of the American Civil War had died down. At the time Russia's position was one of benevolent neutrality, not recognizing the separatists of the Confederacy, which rather astounded the rest of the world as logic would dictate that land-owning Russia would support the plantation owners of the South. Chancellor Gorchakov, however, believed that the USA was the main trading competitor of Great Britain, and in the general scheme of things Europe, and that it was in the interests of Russia to have the USA as a partner, and not an enemy.

There was a special relationship between Russia and the USA because of the sale of Alaska. Russia's logic was simple: to maintain this territory on the borders of the British Empire (to wit, Canada) was in practical terms impossible. And the USA with its territory blocked British access to Chukotka and Kamchatka. This was decades before there was any Atlantic solidarity. There was a Pacific solidarity, however.

Public opinion in the USA, thereby, was wholly on the side of Russia. This explains the reception afforded to the Russian delegation that arrived for the World Exhibition, dedicated to the 100th anniversary of American independence (which, incidentally, at the time was supported by Catherine the Great through 'armed neutrality'). The delegation was promised it would be shown everything that was of interest, and would be helped in purchasing high technology equipment. One of Shukhov's interests was the experience of building oil pipelines.

The Russian visitors to the USA had a friend — Alexander Bary — also a remarkable individual. He was the descendant of French immigrants who had fled to the Russian Empire from revolutionary France, but through an irony of fate Alexander Bary's father himself flirted with Marxism, and after, he became the focus of interest of the Tsarist police in 1863 , deemed it prudent to leave for the USA. Therefore Alexander, born in St Petersburg, educated in Zurich, moved to be with his family in the USA, where he took American citizenship. This, however, did not prevent him from being a Russian patriot and help his friends in their mission.

Bary's life in the USA was a good one — his work was with construction metals at the Exhibition earned him a gold medal as reward. So this man arranged for the Russian delegation not only a schedule of equipment purchases, but also special excursions to refineries and pipelines. Shukhov saw what could be developed in Russia, in Baku, and also what could not appear soon enough. But at the same time he identified some loopholes in the decisions made by the Americans... He would correct them, but not just now. Because order is order, and after this wonderful trip it was time to do the work he had been assigned to do. But a dream had emerged, which, moreover, began to acquire a definite form.

The road to one's dream is never straight. On returning from the USA in 1877 the gold medalist was assigned to the draughtsman's office of the Warsaw-Vienna railway line. A routine of necessary but routine projects began — bridge crossings, water supply stations, station buildings and separate toilet facilities. A Shukhov family friend, the famous surgeon Pirogov, heard about the young Vladimir's frustrations, and advised him to busy himself with something more engaging — for a start, to go and attend a surgery course in the Military-Medical Academy.

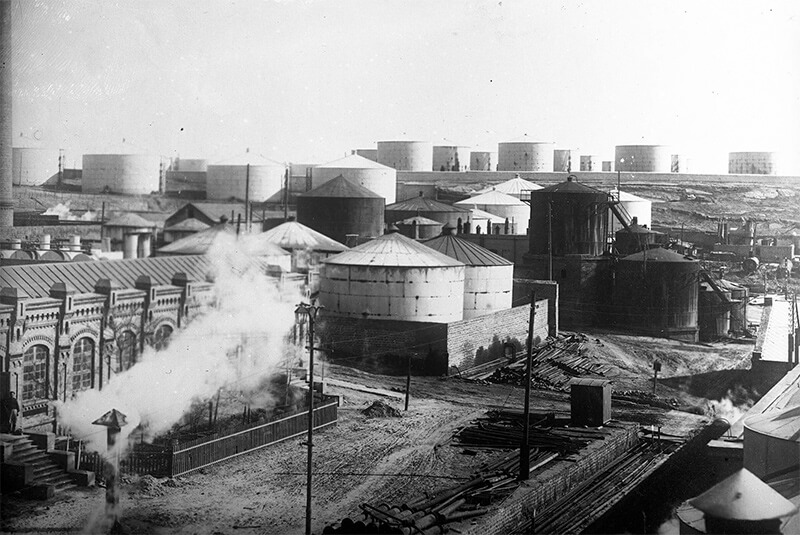

Bary's arrival saved Shukhov from routine or surgery — together with his family he returned to Russia. The passport of a citizen of the United States protected him from any possible security issues, and he was able to give himself over entirely to business. Bary realized that Russia was only at the very start of its industrial development, and here he could, using American experience and methods, make progress very quickly. The commodity with the greatest potential at that time was oil. The Baku oilfields, however, were in a surprisingly archaic condition.

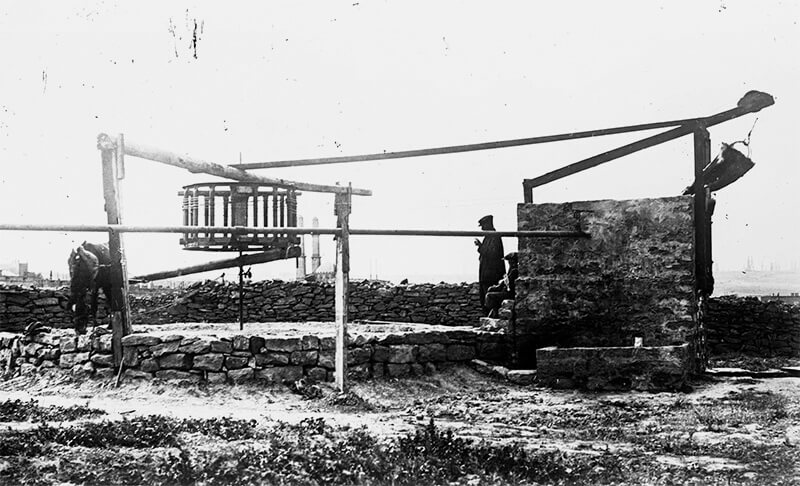

It is a myth that oilmen must always support progress. Big business is a system of agreements, many of which are calculated for decades in advance, loans and connections. In the short term breaking something up does not always look to be profitable. Thus, oil extraction on the Apsheron peninsula was carried out in the most primitive way: from wells or shallow drillholes, using the most labour-intensive methods. The oil was then poured into casks, loaded on to horses and taken to the coast, where it was evaporated into kerosene. Two thirds were poured away into huge lakes.

During Mendeleev's trip oil was valued for refining, where it was boiled and turned into kerosene, at about 30-40 kopecks per pood (which was commensurate with the price of wheat flour) or, if valuing it by today's standards, approximately from 2 roubles 60 kopecks to 3 roubles 40 kopecks a barrel. That said, the price of kerosene in the central part of Russia rose to 4 roubles per pood — in other words, the finished product cost 10 times as much.

It is true that at the time the word 'kerosene' was not known in Russia. It was a trade mark in Britain, where the liquid for illumination lamps in Russia was given a very pretty name — 'photogene', which in translation means 'light-producing'.

Given that, kerosene lamps of that time when burning used up about 50 grammes per hour, a kilogramme of kerosene sufficed for approximately 20 hours, that is, one hour was a little more expensive than 1 kopeck. A kopeck, however, back then in Russian markets was worth quite a lot 'in weight'.

It was clear that any profit from kerosene production was essentially eroded through the number of middle-men and third-party participants of this archaic technological chain, including manufacturers of timber for the barrels, coopers, and specialists in cask stitching.

It is difficult to describe the scale of underhandedness of the business in Baku 150 years ago. All participants of the production process the authorities and supervisory bodies were simply intertwined in an infernal morass that had been largely brought about by the system of buy-backs which at that time determined how the oil fields were distributed. In and around Baku a number of small enterprises operated which engaged in vicious competition with each other, with competitors' wells and refineries set on fire, potential newcomers were 'squeezed out' as a matter of course, and there were kickbacks to administrators. The most powerful force was the army of more than10 thousand carriers of the oil, organized by powerful local forces, to all intents and purposes a transport mafia. Defeating it seemed impossible.

There is a story, that in 1870 a mechanics factory in St Petersburg belonging to the Swedish-Russian family Nobel received a new order to manufacture weaponry. This was something rather routine for the Nobels — back in 1842 Emmanuel Nobel came to Russia and began the production of weaponry and naval mines. His sons, Ludwig and Robert continued their father's work but leaned more towards mechanics, just as Alfred, the future founder of the Nobel Prize, leaned more towards chemistry, with the creation of new types of explosives.

Thus, Robert Nobel travelled to the south of Russia to purchase walnut-tree wood for the manufacture of rifle stocks at the family's factory. Along the way he made the acquaintance of a Dutchman, who produced oil on a rather small scale in Baku. As he listened, enthralled, to the Dutchman's story, Robert decided to get involved in this new, and promising business, seeing larger possibilities there than the compatriot of Till Eulenspiegel could even imagine, who himself had by now grown tired of Oriental exotica and was glad to sell Robert his small refinery.

The fact that the Dutchman had good reason to flee Baku, notwithstanding the seeming profitability of the oil business, became clear to Robert Emmanuelovich very quickly. Either the Nobels had connections at the very top, including the Sovereign himself, or complaints against the oil buy-backers had reached the most entrenched government civil servants, but in 1872 the system of buy-backs was abolished and the oilfields were privatized. In 1873 the first auction took place. Ownership was, however, encumbered by a special tax — 10 roubles per decima (1.1 hectares) every year and indefinitely.

Robert was able to modernize his factory and in1875 put on sale 300 barrels of good kerosene. It was then that his brother Ludwig took an interest in the business, not only a talented engineer, like Robert, but also a businessman of some acumen, and he began to analyze the whole technological chain of production, beginning with oil extraction, its transportation to oil refining facilities, the refining process, transportation to central Russia, distribution, and advertising the product. The Nobels began actively studying the American experience, and it was here that Vladimir Bary and Vladimir Shukhov crossed their paths — young, imposing and already successful engineers.

The young men acted fast. Alexander Bary in 1877 opened in Baku a branch of his construction firm, whose chief engineer was Vladimir Shukhov. Bary and Shukhov assessed the situation quickly and realised that here was an untapped source of work, where they could apply the skills they had learned in the USA. But knowing Russia well, they realized that you can't chop wood with a penknife, and they would have to be circumspect, securing support from influential forces.

The young men acted fast. Alexander Bary in 1877 opened in Baku a branch of his construction firm, whose chief engineer was Vladimir Shukhov. Bary and Shukhov assessed the situation quickly and realised that here was an untapped source of work, where they could apply the skills they had learned in the USA. But knowing Russia well, they realized that you can't chop wood with a penknife, and they would have to be circumspect, securing support from influential forces.

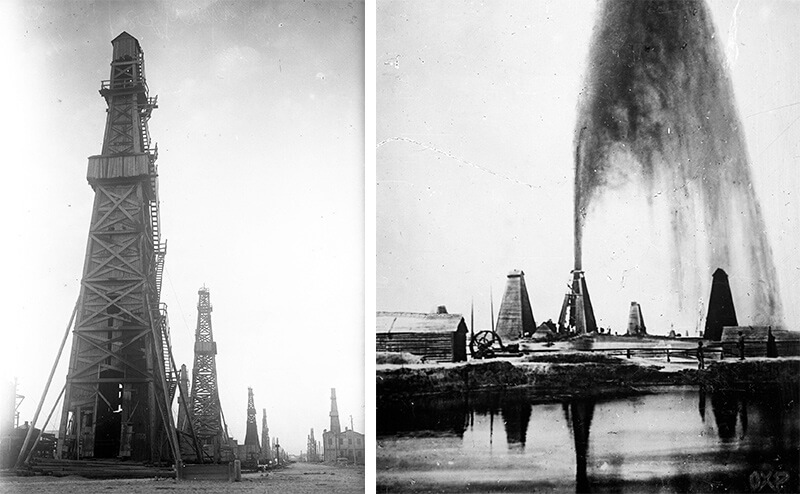

Ludwig Nobel immediately saw the significance of the proposal of Bary and Shukhov to replace barrels with a pipeline. References to the American experience also helped, as did those to Mendeleev's authority, whose name was by now known throughout the world. Bary and Nobel drew up a contract to construct a pipeline from the Baku oilfields to Nobel's factory in Black City with a throughput capacity of 50 tons per hour, and engineer Shukhov, just turned 25, obtained total freedom for engineering decisions.

But having freedom for engineering decisions and freedom of action are two very different things. The idea of laying down a pipeline immediately ran into opposition from the authorities. And not because they were against technological progress per se, or were disconcerted by the American citizenship of Mr Bary. They feared a social explosion, and possibly the collapse of all the networks of corrupt relationships that had been established.

It did not take a genius to realise that a pipeline would make thousands of oil carriers redundant. And it would be not only the carriers who would suffer, but also those who controlled the business, and had close ties with the local administration. The mooted changes were greeted with apprehension by the public, and both the public and the authorities were alarmed at the prospect of mass disturbances, unemployment and even ethnically-grounded conflicts. Things came to a head with a threat to forbid laying a pipeline that was situated on state property. It was clear that what was at stake was not only the construction technology, but also the technology of promoting innovation, in other words marketing.

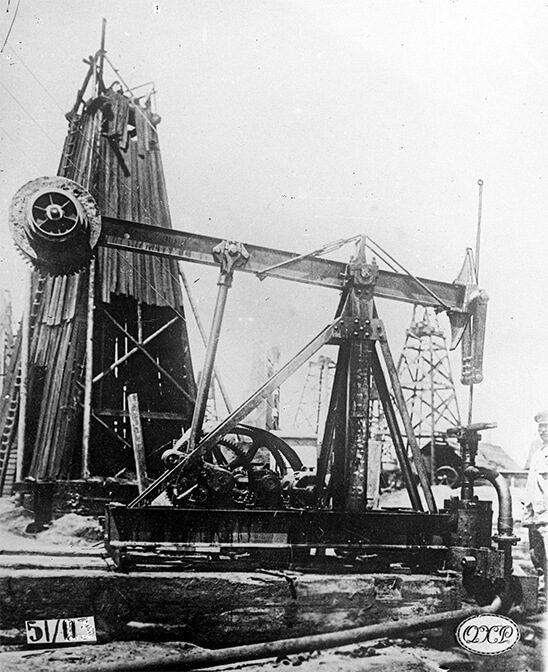

Shukhov wasted no time. As a matter of course he could tackle several issues at the same time, and could just about do everything himself, whether it be examining the finished product, or getting his hands dirty at the manufacturing lathe. He wasted no time in ordering pipes for the pipeline in the USA, the cheapest but also the best quality available. Welding had yet to be invented, so the pipes were connected by threaded joints aided by sockets.

The length of the pipeline with the technical releases was little more than 12 kilometres, the diameter of the pipe was three inches, which is to say 76 mm. In other words the pipe itself was considerably shorter than the longest American pipes. Yet this first pipeline was being built by a young man in whose idea very few people in Baku had much confidence.

Attitudes towards him were not even scepitcal, but outright hostile. This young man had the temerity to break down established traditions! The circle of the disaffected was getting larger all the time: the carriers were joined in their opposition by the owners of coopers' businesses who manufactured barrels, and armator offices, all of them fervently hoping that Shukhov's project would founder.

Even Ludwig Nobel, who handled the business aspects, was uncomfortable. Nobel initially invited other oil entrepreneurs to invest in the business by buying shares, as their profit margins were being hit by the tactics of the carriers. But his colleagues and competitors simply took fright at public opinion, and the possible consequences for them personally. Rumour has it that other entrepreneurs simply said: 'You Swedes can leave at any time for St Petersburg, or your homeland...Our homeis here, we have to live here, with these people...'

As a result Nobel began financing the pipeline on his own. No sooner had construction begun than the warehouse where parts imported from America were stored burned down. The pipes that had already been laid were drilled at night, and connecting points were covered with acid. Nobel was beside himself, but was not prepared to turn his back on the project.

Shukhov noted that among the carriers there were those who wanted something better in their lives than pulling barrels from the fields to the factory. They had been hired on good wages to carry the construction materials of other workers, and they got clean drinking water and foodstuffs. Nobel paid more, and qualified workers were among the elite of the working class. Nobel hired Cossacks to protect the pipeline, and set up watchposts and towers along the pipeline's route.

While Ludwig Nobel organized the work on the pipeline, Vladimir Shukhov completed its construction in only a few months. The year 1878 entered the annals of the history of the Russian oil industry. The Nobels' colleagues and competitors were amazed, and realized what an opportunity they had missed by not investing in such a profitable enterprise.

But the Nobels to everyone's surprise announced that they would pump the oil of all who so desired. For only five kopecks per pood (instead of 20 kopecks for it to be transported by the carriers was an excellent saving). The next year the Lianozov oil company placed an order with Bary's firm to build just such a pipeline, but several kilometres longer. Another 10 years later near Baku there would be 25 pipelines totalling around 300 km in length, transportation costs would drop to a mere 2 kopecks per pood, cheaper than the cost of extracting the oil. But Shukhov did not build these new pipelines, because after building the first ones he became involved in other aspects of the business, entering hitherto unexplored territory where his American experience was of no help to him...

It should be said that the American experience could also be a hindrance. The secret was simple: the oil pipeline business in the USA was started up by dynamic but poorly educated entrepreneurs. There was a famous incident, when during the winter a pipeline ruptured that had been laid in the summer, and then with the onset of the summer heat a 'winter' pipeline buckled and snaked out and along a road, destroying neighbouring houses simply because the builders had not taken into account the fact that metal expands at different temperatures.

Shukhov was a real engineer of the European school. He had a great command of mathematics, with a sound knowledge of physics and chemistry, and was able to converse in three languages fluently, he was a keen student of the contemporary professional literature, and he understood the complexity of the processes with the pipeline and inside the pipeline. And, incidentally, around the pipeline also. He not only designed the pipeline, Shukhov also designed the business. Like his intellectual 'guru' Mendeleev, Vladimir Shukhov saw in science a tool for entrepreneurship.

Shukhov considered the pipeline as a system consisting of two stations: one transmitting, the other receiving. In order to pump oil along the pipeline, pressure had to be created in the transmitting station. But only thick pipes could withstand high pressure. Such pipes were more expensive, they ruptured more frequently and assembling the pipeline became more expensive. In other words, the system threatened to become uneconomical. There were several possible solutions: to have additional pumping stations or to increase the temperature of the oil being pumped. Or the fuel oil.

Fuel oil at the time was considered not worthy of attention. Fuel oil was what remained of the refining and release of kerosene cut. A thick mass, thicker than oil. But the more Shukhov worked with oil, the tougher it was for him to see that only part of it became the actual product. Fuel oil also had to be used to bring in a profit. For instance, as fuel for the steam pumps which pumped the oil along the pipelines, for any other steam utilities, including the steam ships that carried the prepared kerosene across the Caspian Sea to the ports of the Volga.

The young Shukhov had once designed a steam atomizer for the burning of fuel oil. Ludwig Nobel bought the patent for it from Shukhov for use in his refineries. So a fuel oil pipeline now had to be built. And Vladimir Georgievich again sat down to his calculations. He already knew that the viscosity of fuel oil was reduced at higher temperatures so it was easier to be pumped. He deduced the dependence of the pipes' diameter, the temperature and the amount of fuel oil used. For extra economy he proposed heating the fuel oil with steam from the steam pumps, which pumped this very fuel oil.

Shukhov went further and examined the correlation between the expenditure of fuel oil for heating the fuel oil pipeline, the pipes' diameter, the distance of the pumping transit and other parameters, and gathered it all together in a table which is still relevant today.

It wasn't only transportation problems that had to be solved but also issues of storing the oil and its products. In Baku oil waste, in other words fuel oil, was poured into pits, and the finished product was kept in barrels or strong rectangular tanks on a thick, solid base. But Shukhov was a mathematician, and in his view a solid base was ungainly and unpractical. And expensive. It was not needed, what was needed was a platform filled with sand, with a flexible steel sheet placed on it and a concrete ring along the sides. Indeed, the walls would also be made of steel rings, and the higher they were, the thinner they were. This was because the pressure of the liquid in the upper part is always lower than at the base. This idea was like a bolt of lightning. It was not long before everyone started ordering new oil storage facilities from Bary's engineering company. Up to 1917 Bary's firm would build 20 thousands of similar reservoirs. Their design would set the international standard. In the film 'White Sun of the Desert' comrade Sukhov would hide Abdullah's wives in just such a reservoir. Even today oil storage facilities are made according to this principle.

One more problem remained: transporting the kerosene to the consumer. At the time kerosene was poured into barrels and loaded on to sailing vessels that travelled to Astrakhan, where the barrels were loaded on to barges which were pulled up river by barge haulers similar to those in Repin's famous painting. The cost of the wooden barrels was about half the value of the kerosene they contained. Steamers solved part of the problem, but not all of it.

The problem of supplying to the lower reaches of the Volga Ludwig Nobel solved himself, with an order to the Swedish shipyard Lindholmen-Motala in 1878 for the world's first oil tanker, the bulk oil carrier 'Zoroaster' , which was meant to transport oil in tanks, that is, in compartments in its hold. Determined to have no further dealings with wooden barrels, Vladimir Shukhov began designing custom-built tanker-barges for navigating the Volga. The oil business began to bear a surprising resemblance to what we see today. Or was Shukhov simply ahead of his time?

Shukhov lived a long and suprisingly full life. He created a system of extracting oil from wells, he invented oil cracking, which would be recognized by the International Patent Court of The Hague in 1923 . He would design the major oil pipelines of Baku-Batumi and Groznyi-Tuapse, whereby, the first would come into commission in the Tsar's lifetime, and the second after the Bolshevik Revoution...

He would continue to build and build. He would invent the construction hyperboloid, not a machine of destruction, but a construction system. The Shukhov Tower, the Volga columns, the Adziogol Lighthouse near Kherson — all of them are hyperboloids designed by the engineer Vladimir Shukhov. When you go into GUM, look up and you will see a glass roof — this is also Shukhov's design. The Kiev railway station in Moscow and the Moscow Telegraph Office, the Moscow Arts Theatre and the Pushkin Museum in Moscow. He created so much that it difficult to pinpoint where precisely in construction he left his footprint. For wintry Russia he created his own version of a central heating boiler, and in 1900at the World Exhibition in Paris he received the gold medal. These boilers are still in use, and the principles of their construction are used in modern boilers.

He was not a businessman, but the most successful of them admired his talent and queued up to, have their orders accepted by him. He agreed that he was exploited, but he also exploited his clients who financed his most audacious projects. He made a career, won laurels, attained international professional recognition, and not once betrayed his own principles.

◼