A boy from a small village in Azerbaijan could in all probability become involved in the oil industry in the oilfields of Baku. But life has its own ways, and he found himself prospecting for oil in Siberia, where he in fact discovered it. His name became a symbol for the most romantic period of Soviet history, when physicists, lyric poets and geologists seemed indeed to be creating a new society.

The history of great discoveries is above all the history of those people who make them, and this in turn is often a succession of chance events. The fate of this boy from the small village of Morul in the northern foothills of the Lesser Caucasus was largely determined by one act carried out by his uncle Suleiman. In line with family traditions, Suleiman was entrusted to go to the town of Ganja with a part of his already small herd as an offering to the local mosque. Suleiman objected to this, and the mullah arrived to deal with the recalitrant young man. Suleiman now did something else that changed not only his life, but the fate of his descendants - he set his dog on the mullah.

In the Russian Empire respect for traditional religions was a very serious matter, and Suleiman's act was punished in the most severe manner. The seventeen-year-old youth was sentenced to 20 years of hard labour. In 1888 he set off for Siberia.

In the end, there was nowhere in Siberia that Suleiman's tracks couldn’t be found. Word had it that he even got as far as Sakhalin, which was at that time the centre for hard labour in the Far East, and even saw and associated with the great Russian writer Anton Chekhov there. The years went by, and Suleiman got used to life in this astonishing land. He learned Russian and the traditions of the Siberians, he liked this rugged but stunning landscape, the customs of the local people, representatives of the most diverse peoples settling in this amazing land, whether it be by their own free will or otherwise.

With the beginning of the Russo-Japanese War came a chance to reduce his sentence, and Suleiman signed up as a volunteer. For his bravery in battle he received several honours, the most important of which was his freedom. It was here that he met the love of his life, a Russian woman called Olga, who travelled back with him to the Kura valley and took the name Feruza. She bore Suleiman nine children, including the father of our hero, Kurban. And on 28 June 1931 Kurban was delighted to see his own first son come into the world. This was Farman Salmanov, the man who would change the history of this huge country.

As a young boy Farman heard his uncle's stories about the astonishing land of Siberia: the astounding beauty of this far-away place and the riches this magical land boasted.

This was the early 1930s, when literally every day newspapers and radio reported on the latest successes of the Soviet people. Exploration of the Arctic and the expanses of Siberia was a state affair. Not many people realised that behind the reports of derring-do there lay an entirely different truth … Farman found this out when in 1937 his father was arrested.

Aged only six Farman became his mother's main support as the eldest child of the family. The need to earn some money did not extinguish his interest in the mysteries of Siberia. He asked his uncle, a schoolteacher, if he could find him books on Siberia and the Far East.

Through his dealings with uncle Suleiman Farman knew Russian better than all the other schoolchildren, and could therefore read literature that was quite complicated. His uncle brought from Baku some books by Vladimir Obruchev, a well-known Russian geologist and exponent of popular science, which were devoted to studying Siberia. The curiosity of a child began to change to the interest of an adolescent and then young man who was growing up in very difficult conditions.

In 1941 uncle Suleiman died. Soon afterwards the Great Patriotic War began. Children also helped adults as much as they could. What is surprising is that after study and work Farman still had the energy to visit a natural history study group and go on hikes in the mountains in order to collect samples of minerals and rock formations. Many years later Farman Salmanov would talk about how happy he was when he brought home to his mother pieces of quartz which would give off bright sparks when struck, and this primitive flintstone could be used instead of matches, which were in terribly short supply at the time.

During the War Farman realized just how important oil was for the country. Oil in Azerbaijan was not just a useful fossil fuel but also part of that land's ancient history. Working in the oilfields was something natural for a young Azerbaijani lad. Butu Farman was deep in thought about where else on the territory of the Soviet Union there might be oil deposits. In the Volga or Urals regions, the Komi peninsular,… where else?

In 1946,a year after the end of the Great Patriotic War, elections were called for the Supreme Soviet of the Soviet Union. Despite the absence of any real political alternative in the elections, there was considerable individual ambition, which spurred candidates to travel around constituencies in order to listen to the "mandate of the people".

The candidate for the constituency of Shamkhor region was Nikolay Baybakov, the eminent People's Commissar for the oil industry. At that time he was only 35 years old. Baybakov was a favoured son in Azerbaijan: he had been born in 1911 near Baku, on the Apsheron peninsular in the small settlement of Sabunchi. In 1942 he had been entrusted by Stalin to organize the evacuation and if necessary the destruction of the North Caucasian oilfields, given the following alternatives: "if you leave the working wells for the Germans intact you'll be shot, and if you disassemble the equipment prematurely you'll also be shot". Baybakov carried out the command of the Supreme Commander-in-Chief and many other instructions. Thus, the candidate had an excellent reputation: if he promised something, he would do it.

That is why on the eve of Baybakov's arrival fifteen-year-old Farman, as the best Russian speaker, was given the task of speaking before the esteemed visitor to tell him about the needs of the village and the school.

Salmanov was very nervous and in the end blurted out what he thought was needed off his own bat: an asphalt road to the school and lighting for it. And in everyone's presence he added that he would most certainly become an oil geologist. Baybakov promised to resolve everything (and apparently kept his word), and then said that Farman's choice of career was the correct one as the country needed oil, the "second Baku" was taking shape in the Volga and Ural regions, and Siberia would be the next port of call...

After graduating from school, Salmanov enrolled in a petroleum institute. There he found himself at the epicentre of discussions on the nature of oil and the means of opening up the boundless expanses of Siberia. The truth was, however, that he was not being sent to Siberia, and Farman Salmanov appealed for the second time to the all-powerful Baybakov in a private letter, asking for assistance in being posted to Western Siberia. Baybakov helped here, too. Salmanov saw with his own eyes that the exploration of Siberia was not only scientific romanticism, but also the clash of theories, interests and ambitions.

В 1910 году Иван Михайлович Губкин заканчивает Санкт-Петербургский горный институт. В отличие от своих сокурсников он выглядел уже «стариком» - ведь на момент окончания института ему было уже 39 лет. Но он свое позднее вступление на геологическую стезю компенсировал совершенно грандиозным трудолюбием и феноменальной интуицией.

The history of how two theories on the origins of oil developed is worthy of a whole novel. To keep a long story short, however, for more than a hundred years two theories have been in conflict: non-organic and organic. The non-organic theory, which Dmitry Mendeleev adhered to in his lifetime, assumes that oil is constantly formed in the course of deep-lying processes at the earth's core and in the course of a whole number of successive chemical reactions.

The organic theory of the origin of oil was actively supported by Ivan Gubkin, Russia's most eminent oil expert, who believed that oil was formed as a result of the decomposition of the remains of plants and living beings.

Depending on which theory you believe to be the correct one, the strategy of looking for deposits is then formed logically. In very approximate terms, we can say that the "non-organicists" were of the opinion that oil in Western Siberia should be looked for in, for example, the foothills of the Ural mountains or in Kuzbass.

"The organicists", however, believed the vast plains to have more potential, such as the central part of Western Siberia where since time immemorial oil and gas had been observed escaping to the surface as sedimentary material had been constantly built up there that contained a large amount of bio-organic substrate from the Jurassic and Cretaceous periods, when this territory was the bottom of a shallow sea.

The relations between the two schools were very confrontational. The same data were interpreted differently by representatives of the different schools. This was called "demonstrating fidelity to one's principles". Scientific disagreements were further compounded by the economic interests of the different organizations, as well as personal ambition.

Furthermore, drilling work in the central part of the Western Siberian plain, in the area of the Ob river, was very expensive, much more expensive than on the plain's periphery, the Kuzbass or the foothills of the Urals. Also, there was the traditional bureaucratic leapfrogging as some industrial geological institutions opened while others closed.

Farman Salmanov was himself a firm supporter of the organic theory and even devoted his diploma project to something that officially did not exist: the oil-bearing region of the Central Ob area. Despite the objections of his professors, he insisted on retaining his own personal conclusions in the text. The obstinate young man was sent to the place where oil was supposed to be found: Kuzbass. In his own words, he wasted two years there drilling in vain where there was no oil and no prospect of oil. Salmanov did not keep his counsel and wrote to various authorities complaining that he was engaged in a totally hopeless undertaking. The matter reached the District Committee, which was a very serious affair as Party bodies in Soviet times held a great swathe of powers. Farman Salmanov evidently felt that his hour had come. He made his famous "escape".

Many sources describe Farman Salmanov's famous navigation to the banks of Surgut along the river Ob as a real pirate raid. He commandeered a barge, loaded on to it his drilling equipment, moored on the riverbank and began drilling. Sure enough, the long-awaited Siberian oil poured forth, he sent a telegramme to Khrushchev and was soon world-famous. That's not quite what happened. It's probably logical that legends don't need boring production details. All the more as Salmanov sailed off with his colleagues at his own peril and risk. He could have been dismissed from his work, even put in prison.

But still Farman Salmanov was no adventurer looking for oil "per se". He was a Soviet citizen to the highest degree and was digging for oil for his the sake of his vast country. He was also acting in the interests of his country. Especially as he was a professional, if still quite young by contemporary standards.

In 1955, aged 24, he was already the head of the Plotnikov and Gryaznensk oil and gas exploratory expeditions which were operating in the Kemerovo and Novosibirsk districts. The secret of his success was simple: the War had wiped out the specialists and those who had the knowledge and were ready to take on the weight of responsibility got the chance to take over. We should remember Nikolay Baybakov here, who became People's Commissar (Minister) for the oil industry aged only 31.

By 1957 Salmanov had already carved out a serious reputation as a skilled leader and a hot-shot specialist. The fact that exploratory drilling in the early 1950s brought no results in the Central Ob region Salmanov put down to the wrong choice of location, poor work organization and insufficient equipment. He also made use of his official status, which provided him with very broad powers.

The semi-legal relocation to the banks of Surgut had been prepared in advance, it was not an impulsive dash. He had agreed beforehand with the local rivermen and received barges and a tugboat, loaded on board equipment for the construction of housing for the drillers and their families, a sawmill, a forge and much more besides that was needed to develop the infrastructure of a new site for more than one hundred people.

The leadership soon found out about Salmanov's willful actions, but decided against setting in motion any repressive measures. Salmanov was inspired by Gubkin's theories, whose name carried much weight for oil workers, but on the other hand two years unsuccessfully looking for oil in Kuzbass enabled much thought to be given to what public money was being wasted on. The self-assertive Salmanov was entitled to some luck. It is hard now to say which arguments prevailed (there are various versions), but the powers-that-be formalized post factum the instruction to redeploy Salmanov's expedition to Surgut. That was in August 1957.

Only with the next navigation was the equipment delivered and what is known as orientation drilling began. The chorus of sceptics got louder and louder, foretelling a sad end to the Salmanov saga. Rumours circulated that soon his case would be taken up by the public prosecutor for the inappropriate use of state funds. Even so, those funds were not enough, and occasionally the oilmen had to resort to some strange "barters". On one occasion one and a half tons of steel cable had to be delivered from Surgut to the drill sites, but there was no transport. An agreement was brokered with the chiarman of a local collective farm who provided horses to haul the cable by pulling, but in exchange the geologists had to reshoe them all.

1959 had come and gone and 1960 was coming to an end. The exploratory wells had not yet given out any oil. Each new day the voices of the sceptics grew stronger, calling for the work to be terminated. The geological exploratory mission had its funding cut, and instructions came from Moscow to wind down the work. Then Salmanov gathered his team together and proposed drilling another couple of boreholes "for good luck", though there was nothing fortuitous about it as there was a good chance of striking oil. The best chances were in the Megion field near Nizhnevartovsk. In the course of drilling two horizons had already been opened, but they gave out only small spurts, not quite what was needed. Something similar had been observed previously, before Salmanov's arrival. What was needed was a stable and abundant flow of oil. Finally, a decision was reached to open up one more potential horizon. 21 March 1961 a fountain was unleashed.

There are many versions of the famous telegrammes Salmanov sent to every possible level of manager and authority. To his scientific opponents he wrote: "Dear comrade, in Megion at well no. 1 an oil fountain from a depth of 2,180 metres is gushing forth. Is it all now clear? Respectfully, Farman Salmanov". To the Directorate of Tyumen Geology he sent a radio telegramme with the message "The well is gushing in due fashion!", and to Nikita Khrushchev "I have found oil! That's that! Salmanov".

There are also different versions of what happened next in those hours and days. Witnesses told of spontaneous rejoicing in a local club which spilled over into just such a spontaneous rally much enlivened by the champagne Salmanov had delivered. What is factually accurate is that Salmanov also reported the discovery to Alexander Protazanov, chairman of the Tyumen Regional Executive Committee. According to Salmanov, Protazanov, though himself a mining engineer by training, did not grasp the full import of what was happening, but cottoned on to the quite lengthy report and made arrangements to fly to Moscow and report to the relevant authorities. By the time he was due to fly out it was already clear that the Megion oil was high quality, and the fountain was still gushing from the well.

In the end Salmanov was required to report to the Kremlin, and to Nikita Sergeevich Khrushchev himself. Surprisingly, Khrushchev praised the oilmen and castigated Nikolay Baybakov, who was accompanying them as the former "oil" minister and former head of the RSFSR Gosplan. It turned out that Baybakov, whom Khrushchev had sent to build sugar factories in the south of Russia in the office of the Krasnodar Council of the National Economy, had "missed the boat" on the Western Siberian oil.

However, after his short tongue-lashing of Baybakov Khrushchev again had a change of heart and praised Farman Salmanov and his colleagues to the skies. It was particularly important that according to Khrushchev the whole world should know about this discovery, because it was yet another success of Soviet society, and the Party and entire nation could be proud of it. Thus was started the blanket coverage of the oilmens' successes in the Soviet press, and soon afterwards the international media. The "Third Baku" dreamt of by Academician Gubkin, became a reality.

Years later Farman Salmanov came to the conclusion that Khrushchev, despite being obsessed with sending a man into space, realized after Protazanov's first report just how important a trump card had suddenly fallen into his hands. A lot of oil offered the solution to a lot of problems that were engulfing the country. Many regions were suffering from shortages of the most basic goods. And if the first Sputnik and the "Thaw" had improved the nation's morale, hard-currency earnings would allow the material issue to be solved.

Много нефти — это решение целого ряда проблем, которые вовсю наваливались на страну. Во многих регионах были уже проблемы с поставками самого необходимого. И если первый спутник и «оттепель» улучшали моральное состояние народа, то валютные поступления позволили бы решить и материальную сторону вопроса.

The oil of Western Siberia brought to the fore a whole cohort of Party leaders. On the one hand, of course, the Tyumen District Party Committee at first played a very positive part because it was a real force and one with which the scientific, industrial and even Soviet community had to reckon with. The Party earmarked funds to extend the geological exploration and prompted organizational changes; for instance, the Surgut oil exploration expedition was turned over to the supervision of the Tyumen geological trust. But Party bodies demanded the work be accelerated, more oil to be extracted, new records to be set and it all had to be reported to Moscow. It was not long before problems and strategic needs began to be forgotten amid the clamorous, rousing reports.

The authorities now had in their hands a grandiose instrument for the development of the country, and they went full steam ahead with it. For many years Farman Salmanov was a successful and devoted worker in this field, discovering more and more new fields and multiplying by many times the nation's wealth. He would become a Doctor of Geological and Mineral Sciences, Honoured Geologist of the Russian Federation, a Hero of Socialist Labour, Winner of the Lenin Prize, a corresponding member of the Russian Academy of Sciences...

But that all lay in the future. Right now he needed to open up what the country's natural landscape had to offer. And for that he needed people, lots of people.

The death of Stalin in 1953 and the subsequent amnesties and rehabilitations put an end to the practice of using the work force of the Main Directorate of Camps (GULag). Most convicts were released. But the country still needed many young working hands. And what was no longer possible to get through coercion proved popular by using young people's natural enthusiasm. The opening up of the North and Siberia, which started after the discovery of the Surgut oil, became possible because the younger generation wanted it.

Opening up the virgin lands, damming the Siberian rivers, extracting Siberian oil were key moments in the development of a mass youth movement. It was the world of young, healthy people, truly the "radiant new world". Joy filled millions of hearts. The authorities did everything to stop that flame from going out.

Above all, propaganda highlighted the emotional buzz of pioneering. Any person, even a dyed-in-the-wool pragmatist, can experience the joy of achievement.

Money, fame, respect and the admiration of society are all important, but the feeling of being a "pioneer" is difficult to put into words. And each person who chose the road to Siberia could count on "washing in the first oil from the fountain".

The arts world and the best journalists also championed what people would normally run away from: substandard living conditions, a primitive lifestyle, etc. Pine nameplates, communities of tents, ships sailing up and down the rivers of Siberia, full of young oil workers and construction workers, all this was new and wonderful. Sadly, in practice it became the norm to firstly build the industrial sites (in other words, completely the opposite of how Salmanov began work in Surgut) and only then, under the infamous "leftover principle", to build accommodation and social amenities such as kindergartens, schools, houses of culture, polyclinics and hospitals.

This was the person, for whom the romance of exploration was uppermost, who was considered worthy of the admiration of his peers, the Party, and the Soviet people as a whole. Higher education institutes specializing in geology experienced fierce competition for places, possibly on a par with physics faculties, theatre or flying schools. It was only years later that many of the graduates understood the reason why the country needed so many specialists in geology. The reason wasn't only in the huge amount of work, but also the turnover of personnel. Accidents and disease brought on by the work took their toll of the specialists and workers. Though it has to be said that the vast majority of young people at that time paid no heed to that. They believed that they were doing something important and necessary, and that their children would thank them for what they had achieved.

In 1961 the conversation with Khrushchev almost immediately paid dividends. From out of the blue resources appeared and six months later Salmanov's expedition numbered almost a thousand people. This was down largely to the positive decision made by the special commission headed by Nikolay Baybakov, who had come to inspect the newly discovered fields. It was he who gave the command "get the oil".

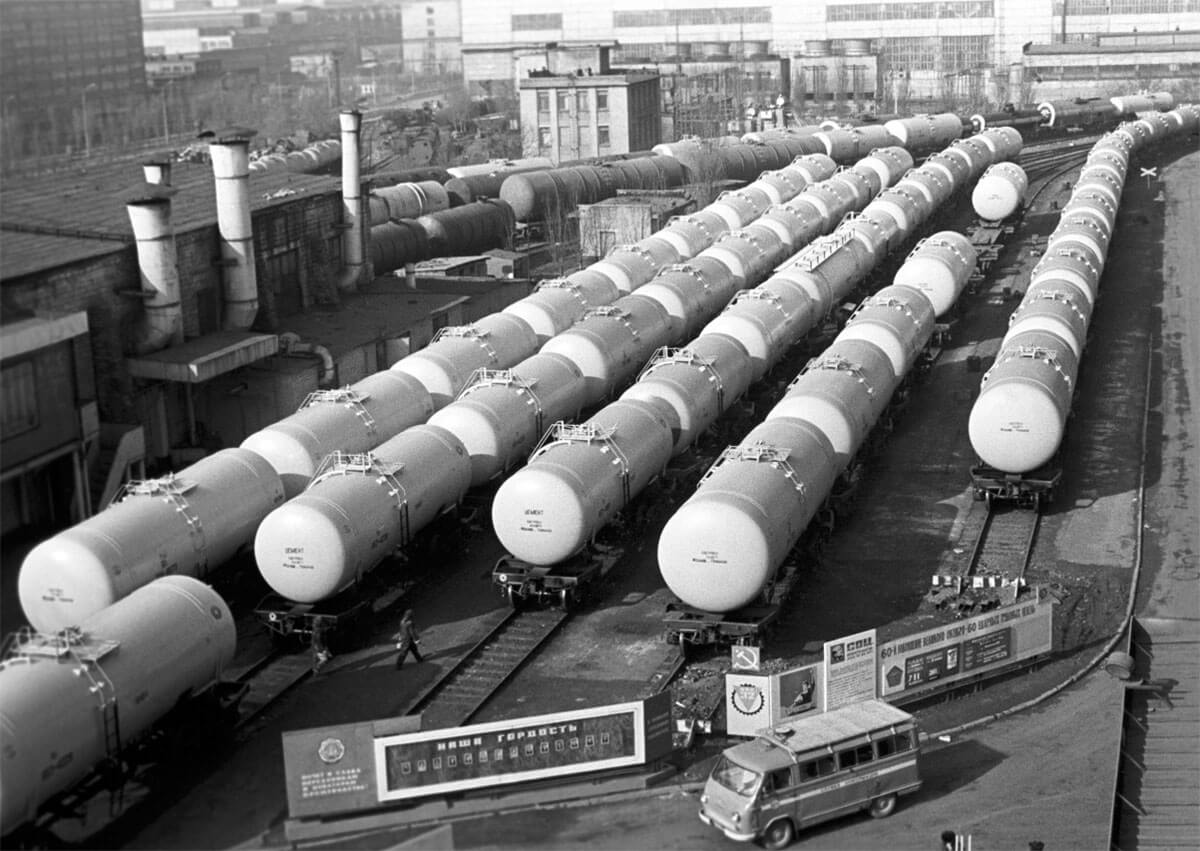

But to get it required the support of the local Party bodies in the person of Comrade Protazanov, thanks to whom it was agreed to build 20 oil-carrying barges at the Tyumen shipbuilding plant. Each barge had a displacement of 2000 tons. On 26 May 1964 the first barge loaded the industrial oil of Western Siberia. It travelled down the Irtysh river to the oil refining facilities. Salmanov recalls that in the first year the fields provided 100 thousand tons of oil, after three years that amount grew threefold, and there were then a hundred local oil-carrying barges. It became obvious that Siberia needed a well-developed system of pipelines.

Years later Farman Salmanov tried to come to terms with the fact that the availability of such wonderful resources was partly to blame for the onset of the subsequent "stagnation". He came to the conclusion that their emergence coincided with the stalling of the Soviet economy in the late 1960s. The reforms introduced by the Chairman of the USSR Council of Ministers Alexei Kosygin were subjected to criticism by the Party leadership following the "Prague Spring", as it became alarmed at the prospect that economic reforms could lead to political upheavals. The once young senior managers were getting on in years, there was no turnover of personnel at the very top, and new ideas no longer were a source of inspiration but rather apprehension.

The Soviet Union was saved from economic collapse by the oil crisis that hit the world in 1973. Oil prices surged, and mega-dollars poured into the USSR. But they were not used judiciously, as it seemed that the oil would last forever, bringing dividend after dividend. The idea of building a just world gradually gave way to the idea of a peaceful, moderately prosperous life.

The enthusiasm of the masses can also be short-lived. Youthful romanticism invariably fades away when families and children appear, and a new way of life requires stability and comfort. But too much was built in a hurry. People yearned to return to their homes, the big cities and capitals.

In the late 1970s the extraction of Western Siberian oil was seen to be in decline. The fields began to dry up. Salmanov more than anyone understood the reason why the oil yields were suddenly reduced. In 1987 Farman Salmanov became the First Deputy Minister for Geology of the USSR. Fate played a hand in bringing him together again with Nikolay Baybakov, as the Soviet government instructed them to produce forecasts on the long-term development of the Soviet Union's fuel and energy complex.

Veteran oilmen spoke of the critical condition of the oil industry, of the necessity to think about its future, and of the danger of reckless extraction of oil in a country that had an urgent need for energy. Salmanov said that in terms of its oil reserves per head of population the USSR was not among the world's leaders, in fact it was not even in the top ten.

However, times had changed, and world oil prices had also. And the country that Farman Salmanov had believed in and and worked hard for disappeared. A new era had arrived, an era of new ideas.

Farman Salmanov was a representative of that generation of Soviet citizens whose lot was to lift up a ruined country, and achieve wondrous success. The first Sputnik, the first man in space, the first atomic ice-breaker and the world's first atomic power station. The world's largest hydro-electric power stations and, last but not least, the huge Western Siberian oil province.

Almost no-one can remember now but 70 years ago the Soviet Union experienced a shortage of liquid fuel. But oil is not only petrol and kerosene, but also the basis for chemical production. A huge amount of what we use comes from oil. The abundance of oil changed the life of the country. If it were not for the oil of Western Siberia, life would have been a lot tougher, that much is clear.

The discovery of oil and gas in Western Siberia played a huge role in global politics, too. The USSR became a reliable supplier of energy resources to Western Europe, which facilitated the consolidation of Europe's economic and industrial power base and the intensification of its integration processes. Western and Eastern Europe were linked by oil pipelines, and whereas once they were enemies they now became partners.

◼